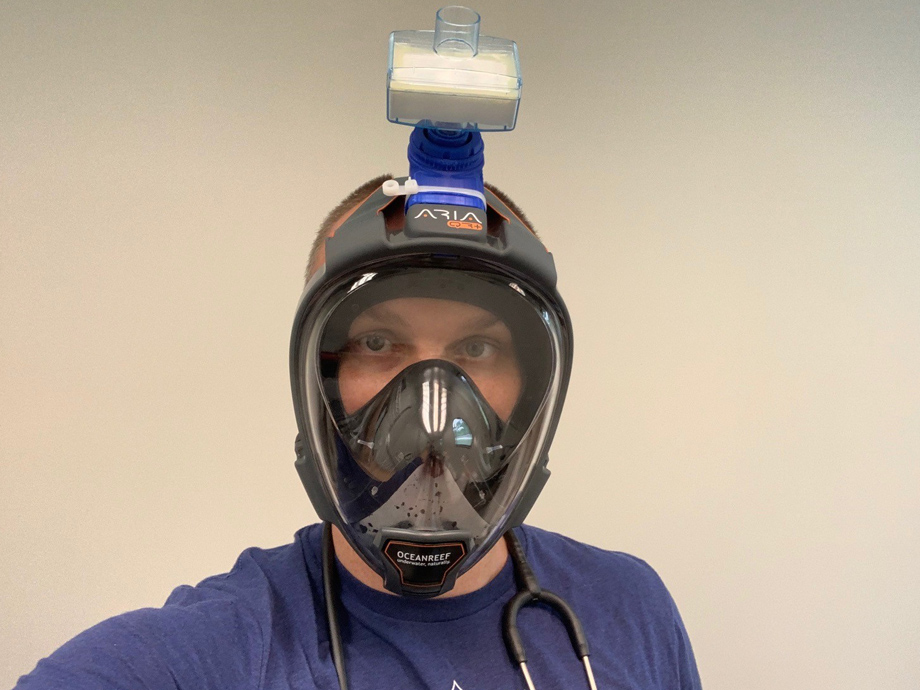

“Seriously, Ryan, what in the heck are you doing?” I thought to myself as I asked the concerned woman about her fevers and recent travels. Then I collected a sample for COVID-19 lab testing.

Although I wasn’t completely confident in my personal protection — which I had read about only a couple of weeks earlier on Reddit and then on an Italian dive company’s website(oceanreefgroup.com) — I felt it was better than my other headgear options. In February and March, I had been using scavenged N95 masks with questionable straps, chemistry lab googles and a surgical bonnet. The snorkel protected my entire face and had been fitted with a 3D-printed adapter (made by a local elementary school teacher) attached to an air filter that, hopefully, was going to clean the air entering my mask and lungs.

And if that wasn’t all nerve-racking enough, a TV news cameraman(www.kctv5.com) was filming the encounter. (I suppose that is what I get for tweeting a picture of myself wearing the DIY mask a few days prior.)

How did it come to this? It’s hard to say. But, it’s now clear that my preparations for a mysterious virus and emerging pandemic, like those of many practices, were woefully inadequate.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, my small direct primary care practice has scrambled to figure out many aspects of our operations. Improvised personal protective equipment — now widely known by its acronym, PPE — was just one of our adaptations. The hurdles have seemingly been endless — logistical, regulatory, scientific or financial, and sometimes all of the above.

Part of the bottleneck was, and continues to be, just truly a lack of available resources — testing supplies, PPE, etc. But I also believe that we, as a medical community, have been unnecessarily paralyzed in some respects.

In a setting with so many unknowns, this is somewhat to be expected. Doctors, like any professionals, want to be confident in what we are doing. That makes sense: If we get it wrong, people may die. And in this setting — with a lack of solid evidence, ever-changing guidelines and a deluge of mixed opinions — how can we possibly be completely comfortable in decisions or recommendations?

“Can I use a nasal saline flush instead of a swab?”

“Which people should we let inside our clinic?”

“Should I test all patients with a cough or only if they have fevers? Or just tell them to isolate?”

“What is an adequate amount of cleaning of rooms and equipment between patients?”

“Does this sick patient need to be admitted to the hospital?”

I didn’t — and often still don’t — have a confident answer to these, and hundreds of other, questions related to practicing primary care in a COVID-19 world.

And that is OK. “I don’t know,” is an acceptable answer when it is the truth.

The history of science and medicine have always been slowly moved toward a better understanding. And here, too, the evidence to support the best approach will inevitably advance. Hopefully, the regulatory morass improves, as well.

In the meantime, we must proceed in a way that is guided by our base of scientific understanding, our capabilities and common sense. We need those now, more than ever. For the sake of our patients and community, we must do the best we can even when it’s uncomfortable; even if it means wearing a non-FDA-approved snorkel mask in a parking lot.

Ryan Neuhofel, D.O., M.P.H., owns a direct primary care practice in Lawrence, Kan. You can follow him on Twitter @NeuCare.(twitter.com)

Read other posts by this blogger.

Comments